Why Treating the Site of Pain Often Fails in Chronic Conditions

The shared frustration

Many people living with chronic pain have already seen many practitioners — physiotherapists, osteopaths, doctors — yet the relief they experience is often only temporary. They have taken medication, followed physiotherapy exercise programmes, and tried different manual therapies, but the outcome is frequently the same: the pain returns, and frustration continues to grow.

Over time, many begin to question themselves. Is there something wrong only with me? Why do others recover after a few sessions, while nothing seems to change for me?

For some, this ongoing struggle leads to the decision to undergo surgery, which unfortunately in many cases does not resolve the problem and can sometimes create additional difficulties.

Now let us change perspective.

As a physiotherapist, osteopath, or medical trainer, you have invested years into education and training in order to help your patients. Most of the people you work with improve — often within just a few sessions. Yet there is a smaller group of patients who do not. They follow your recommendations, they do the exercises, they attend the sessions, and still the pain returns.

This situation is deeply frustrating. You start questioning your clinical reasoning, wondering whether something is being missed. The patient feels stuck, the clinician feels stuck, and over time this can lead to a growing sense of dissatisfaction and even a loss of trust in physiotherapy and rehabilitation as a whole.

In many of these cases, the issue is not a lack of effort, compliance, or professional skill. Rather, it is that something important is missing from the way chronic pain is being approached.

Why focusing on the painful area makes sense

When a patient comes into the clinic with pain, the most natural reaction — for both the patient and the therapist — is to focus on the painful area. If the pain is in the shoulder, the treatment is directed at the shoulder. If the lower back is painful, the therapy is applied locally.

In many cases, this approach leads to very good results. This is especially true in acute situations, such as after an injury or surgery. Local treatment, whether through exercises, manual therapy, kinesiotaping, cryotherapy, or other supportive techniques, plays an important role in the healing process.

In acute conditions, the goal of local treatment is to support tissue healing, reduce irritation, restore function, and prevent unnecessary compensations. Applied at the right time, this approach is logical, appropriate, and often highly effective.

For this reason, local treatment forms the foundation of physiotherapy and rehabilitation practice, and in many cases it is exactly what the patient needs.

The challenge arises not because this approach is wrong, but because the same logic is often applied to situations where the context has changed. When we continue to use an acute injury framework for patients who are dealing with long-standing, chronic pain, the results are often limited or short-lived.

Acute vs chronic pain: when time changes the rules

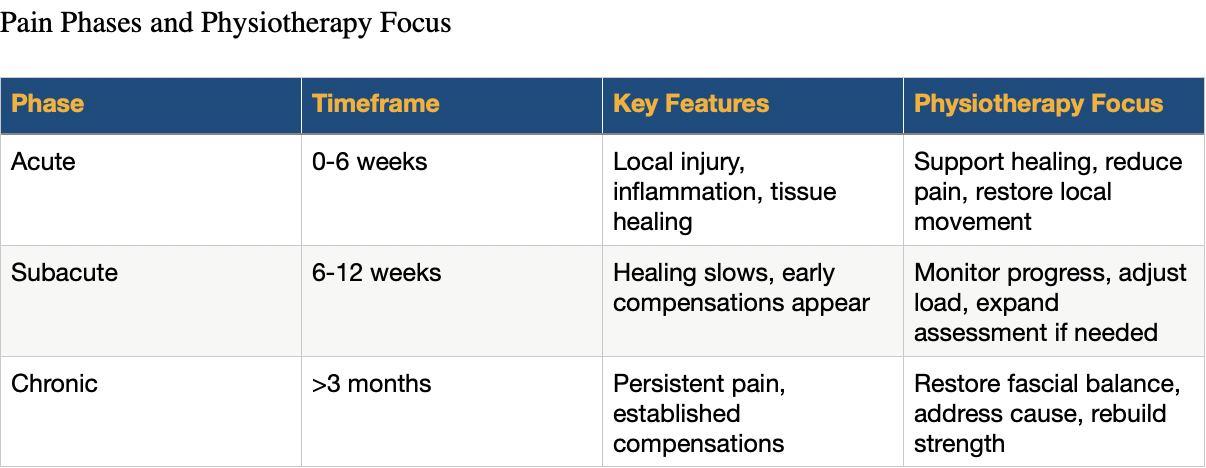

Depending on the duration of symptoms, pain is commonly described as acute, subacute, or chronic. While these phases are defined by time rather than by pain intensity, they reflect important differences in what is happening within the body.

The acute phase typically begins after a clear event such as trauma, injury, or surgery and usually lasts up to around six weeks. During this time, the affected tissues undergo inflammation and rebuilding as part of the normal healing process. In this phase, local treatment plays an important role: supporting tissue healing, assisting lymphatic drainage, restoring movement, and preventing early complications or compensatory patterns.

Beyond this initial period, we enter the subacute phase, which generally extends from around six to twelve weeks. Pain may still be present, but its intensity and quality should be changing over time. Tissue healing is largely underway, yet early adaptations and compensations can begin to appear. Local treatment can still be very beneficial at this stage; however, if it has already been applied consistently and no meaningful improvement is observed, a broader clinical assessment should be considered.

Pain that persists beyond approximately three months is commonly described as chronic. At this point, expected tissue healing timelines have been exceeded. Ongoing symptoms are often accompanied by compensatory movement strategies, altered load distribution, and changes within the connective tissues. In many of these cases, purely local treatment is no longer sufficient to create lasting change.

What defines an “acute injury”?

In my clinical approach, even when pain appears to be acute — for example, starting within the last few days or weeks — I do not assume that it is necessarily caused by a recent tissue injury.

The first question I ask is whether the mechanism of injury was significant enough to reasonably explain the symptoms.

Clear mechanisms such as a sprain, subluxation, direct trauma, or surgical intervention can justify an acute tissue response. In these situations, the pain presentation aligns well with expected healing processes, and local treatment is often appropriate.

However, when the onset is less clear — for example, pain that started after sleeping in an unusual position or during a seemingly minor movement — I begin to look more closely at the patient’s history. In such cases, it is often not a single event that created the problem, but rather an accumulation of compensatory tension and adaptation over time. The “wrong position” may simply be the moment when the system could no longer compensate.

For this reason, I start my assessment by exploring the painful area, but if no clear explanation is found, I expand my evaluation to neighbouring regions exploring the possible tensional compensations.

Chronic pain: why repeating local treatment often fails

When a patient presents with chronic pain and has already undergone multiple local treatments without lasting improvement, I do not begin by repeating another local intervention. In most cases, skilled colleagues have already explored that option thoroughly.

Instead, I shift my focus toward understanding why the pain persists. In chronic conditions, pain is often the endpoint of a longer process rather than the original source of the problem. Identifying the factors that contributed to this ongoing adaptation is essential for creating meaningful and lasting change.

What changes in chronic conditions

When pain persists despite appropriate local treatment and well-designed exercise programmes, it is often an indication that the painful area itself is not the primary driver of the problem. In many chronic cases, pain is a secondary manifestation of something that developed earlier — often as a result of ongoing adaptation and compensation within the body.

Over time, increased tension within tissues, reduced fascial gliding, and altered load distribution can lead to what patients often describe as “knots” or stiffness. Movement patterns adapt, not consciously, but as a protective strategy. Gradually, the body reorganises itself to avoid pain, even if this comes at the cost of efficiency or balance.

When chronic pain is viewed through this lens — as the result of long-term adaptation rather than a local tissue problem — it becomes clearer why purely local treatment is often insufficient. In these situations, we may be treating a structure that is under tension due to forces originating elsewhere, from tissues that have undergone long-standing, and sometimes pathological, compensations.

A clinical example

Movement verification before (1) and after (2) the first session.

To illustrate this, I would like to share an example from my clinical practice.

A 46-year-old man came to my clinic with lower back pain that had been present for approximately four to five months. The pain first appeared when he was placing his newborn baby into a cradle. His back “seized up,” leaving him nearly immobilised for close to a week.

He attended physiotherapy focused on local tissue mobilisation and strengthening exercises. Although he was able to return to work after about a month, he reported that his lower back continued to feel painful and unstable, as though it might “snap” with one wrong movement.

At first glance, the mechanism of injury — placing a baby into a cradle — may appear demanding, but it is not a traumatic event that would normally explain persistent pain of this severity and duration. If the issue had been limited to a local muscle strain, a combination of time and targeted exercise should have been sufficient. Yet the pain persisted and gradually became chronic.

Looking beyond the painful area

The next step in my assessment was to explore the patient’s injury history. When asked about previous trauma, he reported a severe ankle sprain more than twenty years earlier, involving a complete rupture of one of the ankle ligaments. At the time, his leg had been immobilised in a cast, followed by a stabilising boot for several weeks.

A significant injury combined with prolonged immobilisation can lead to increased rigidity and altered tension within the fascial tissues surrounding the joint. Over time, these changes do not remain isolated. Through myofascial continuity, compensation can gradually ascend through the system until it reaches a segment that is less able to adapt — in this case, the lower back.

Treatment focused on restoring function and balance at the ankle level resulted in a resolution of the patient’s lower back pain, along with a full return of movement.

The local treatment of the lower back had not been fully effective because the lower back itself was not the primary issue. The old ankle injury had created fascial rigidity within the retinacula and muscular fascia, limiting the stability and functional capacity of that segment. Over the years, the body adapted by altering how load was distributed through the fascial system.

When the patient became a new parent, the increased physical demands of carrying, lifting, and placing the baby — often in standing or walking — repeatedly stressed a system that had already been functioning under pathological compensation. This explains why a movement that appeared minor triggered such a significant response.

The intelligence of adaptation

It is important to remember that the body is not failing in these situations — it is adapting. After injury, the body seeks small, often unconscious adjustments in movement and tension in order to maintain function and restore homeostasis. Problems arise not because these adaptations exist, but because over time they may become fixed, limiting, and no longer efficient.

Understanding this process is essential when working with chronic pain and forms the basis for approaches that address the body as an integrated system rather than a collection of isolated parts.

This is not “manual therapy versus exercise”

This article is not an argument against local treatment or exercise-based rehabilitation. Both play an essential role in physiotherapy and are supported by strong clinical and scientific evidence.

The key issue in chronic pain is not whether to use manual therapy or exercise, but when and based on what clinical reasoning.

In chronic cases, beginning with a full exercise programme before addressing underlying tissue tension can sometimes reinforce compensatory movement strategies. When fascial gliding is restricted and force transmission is altered, loading the system too early may strengthen existing pathological patterns rather than restore balanced function.

For this reason, in my clinical approach to chronic pain, manual therapy aimed at restoring normal fascial gliding and tensional balance is often the first step. This creates more favourable conditions for movement and load acceptance. Once the tissue is able to adapt more freely, exercise becomes not only safer but significantly more effective.

Exercise is essential — particularly in the later stages of rehabilitation. After manual therapy has reduced excessive tension and improved tissue adaptability, a structured exercise programme helps maintain the achieved results, restore strength, and prevent the re-emergence of compensations.

Research in chronic low back pain has shown that prolonged pain is associated with altered activation, reduced endurance, and decreased strength of the paraspinal muscles, including the erector spinae. This supports the clinical observation that restoring tissue function alone is not sufficient. Strength, coordination, and load tolerance must be rebuilt through appropriate exercise once the system is ready.

Local treatment therefore still has a role in chronic pain, but its timing is crucial. When used as an initial intervention in isolation, it may provide only temporary relief. When combined thoughtfully with exercise — and applied at the right moment — it becomes part of an effective, integrated rehabilitation strategy.

Ultimately, the question is not manual therapy or exercise.

The question is timing and clinical reasoning.

Chronic pain requires broader thinking

Chronic pain requires thinking beyond the obvious. When a patient has already received several local treatments, followed exercise programmes diligently, and yet the relief is only temporary, repeating the same approach rarely leads to a different outcome. At that point, both the patient and the clinician often feel stuck.

If a therapist has treated the painful area multiple times without lasting results, an important question arises: why continue working locally if the problem persists? This is usually a signal to pause and reconsider the clinical reasoning rather than the patient’s compliance or motivation.

In such cases, it becomes essential to ask broader questions. Was the mechanism of injury significant enough to explain the intensity and persistence of the pain? What events, injuries, or periods of immobilisation occurred in the patient’s past that may have altered tissue behaviour over time? These questions often open doors that local assessment alone cannot.

The body does not function as a collection of isolated parts. Through the fascial system, tension, load, and compensation are continuously transmitted and redistributed. When this system adapts pathologically, pain may appear far from its original source. Recognising this allows the clinician to move from symptom-focused treatment toward addressing the underlying cause.

Adopting this broader perspective does not reject local treatment or exercise — it refines their use. For many chronic pain patients, this shift in thinking can be the key factor that finally changes outcomes.

References

• Stecco C, Driscoll M, Schleip R, Huijing P (Eds.). Fascia: The Tensional Network of the Human Body.

• Branchini M, et al. Fascial Manipulation® for chronic aspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial.

• Arumugam K, et al. Effectiveness of fascial manipulation on pain and disability in musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review.

• Scoping review on therapeutic mechanisms of fascia manipulation (manual therapy effects).

• Luomala T., Pihlman M. A Practical Guide to Fascial Manipulation.

• Variation in paraspinal muscle morphology and function in chronic low back pain — MRI evidence.